Tramadol Seizure Risk Calculator

Risk Assessment Tool

This calculator estimates tramadol seizure risk based on factors from clinical studies and FDA guidelines.

When doctors prescribe Tramadol is a centrally acting synthetic opioid analgesic that works on both opioid receptors and serotonin/norepinephrine pathways, offering moderate‑to‑moderately severe pain relief. Its dual mechanism also creates a hidden danger: seizures can happen even at therapeutic doses, especially in certain groups of patients. Understanding tramadol seizure risk means looking beyond the label and spotting the people who are most likely to experience a fit.

Why Tramadol Can Trigger Seizures

Unlike many opioids, tramadol blocks the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine. This boosts pain relief but also lowers the brain’s seizure threshold. Research consistently shows a dose‑response curve - the higher the amount taken, the more likely a seizure will occur. In a 2019 cross‑sectional study of 167 emergency‑room patients, 58% of those who overdosed on tramadol had a seizure, and the median dose among patients with multiple seizures was 2,800 mg, far above the recommended maximum.

Who Is Most Vulnerable?

Three major risk categories dominate the literature:

- Seizure history - patients with epilepsy or prior fits are almost four times more likely to have a tramadol‑induced seizure (OR ≈ 3.7).

- Concurrent use of medications that either inhibit the enzyme CYP2D6 or directly lower the seizure threshold, such as certain antidepressants (fluoxetine, paroxetine, amitriptyline) or antipsychotics.

- Age‑related factors - older adults, especially those with reduced renal function, face higher plasma tramadol levels and are often on multiple drugs that interact.

1. Pre‑Existing Seizure Disorders

Patients with a documented seizure condition have a dramatically higher odds ratio. The Babahajian study (2019) calculated an odds ratio of 3.71 for seizure occurrence when tramadol was added to their regimen. In practical terms, a person who normally has a seizure once a year may experience several fits within weeks after starting tramadol, even at standard doses.

2. CYP2D6‑Inhibiting Antidepressants

The enzyme CYP2D6 converts tramadol into its more potent metabolite O‑desmethyltramadol (M1). When a CYP2D6 inhibitor is present, the conversion slows, leading to higher parent‑drug concentrations - the form more likely to trigger seizures. Wei et al. (2023) examined over 70,000 nursing‑home residents and found a 9% relative increase in seizure rates when tramadol was combined with CYP2D6‑inhibiting antidepressants versus non‑inhibitors. This risk persisted regardless of which drug was started first.

3. Elderly Patients and Renal Impairment

Age brings two problems: reduced CYP2D6 activity and decreased kidney clearance. The FDA now caps the daily dose for adults over 65 at 300 mg (down from 400 mg) and recommends a 30% dose reduction for creatinine clearance between 30-60 mL/min. Renal failure below 30 mL/min is a contraindication. A 2022 label update explicitly links these adjustments to seizure prevention.

4. High‑Dose or Misuse Scenarios

Recreational misuse, especially among young adult males, is another red flag. In the Babahajian cohort, 85% of tramadol‑intoxicated patients with seizures were male, median age 23, and many reported doses exceeding 1 g in a single episode. Overdose studies consistently show seizures within the first six hours after ingestion, with a mean latency of 2.6 hours.

Clinical Presentation and Timing

Seizures induced by tramadol are typically generalized tonic‑clonic and occur within the first six hours post‑dose. They may be single events or recur if the drug is not discontinued or the dose is not reduced. Blood tramadol levels do not reliably predict seizures; the dose reported by the patient is a better indicator, highlighting the importance of a thorough medication history.

Guidelines and Best‑Practice Recommendations

Given the data, several professional bodies have issued concrete advice:

- Screen every patient for a prior seizure disorder before prescribing.

- Check for CYP2D6‑inhibiting drugs. If present, consider alternative analgesics or switch the antidepressant to a non‑inhibitor such as citalopram.

- For patients ≥65 years or with creatinine clearance <60 mL/min, limit tramadol to 300 mg/day and monitor renal function.

- Educate patients about the early signs of a seizure and instruct them to seek emergency care if one occurs.

- Document dosage and any dose changes meticulously; avoid upward titration beyond the recommended maximum.

Risk‑Comparison Table

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio (OR) | Study / Year |

|---|---|---|

| History of seizure disorder | 3.71 | Babahajian et al., 2019 |

| CYP2D6‑inhibiting antidepressant + tramadol | 1.09 (relative increase) | Wei et al., 2023 |

| Age ≥ 65 years + renal impairment | 1.45 (estimated) | FDA labeling, 2022 |

| Dose > 400 mg/day | 2.6 (dose‑response) | Taghaddosinejad et al., 2011 |

Real‑World Stories

Patient forums illustrate the human side of the data. A Reddit user ("PainPatient87") shared that after starting tramadol alongside sertraline, she experienced her first seizure at age 32 and now requires lifelong antiepileptic therapy. In New Zealand’s CARM database, ten seizure cases linked to tramadol were reported between 2002‑2006, half involving doses above the 400 mg daily ceiling and three involving concurrent tricyclic antidepressants.

Future Directions: Pharmacogenetics and Personalized Prescribing

Testing for CYP2D6 genotype could soon become routine. A 2023 University of Toronto study showed poor metabolizers have 3.2‑fold higher tramadol plasma levels after a standard dose, directly tying genotype to seizure risk. The National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke is funding research to create a risk‑prediction algorithm that blends dose, age, renal function, and genetic data.

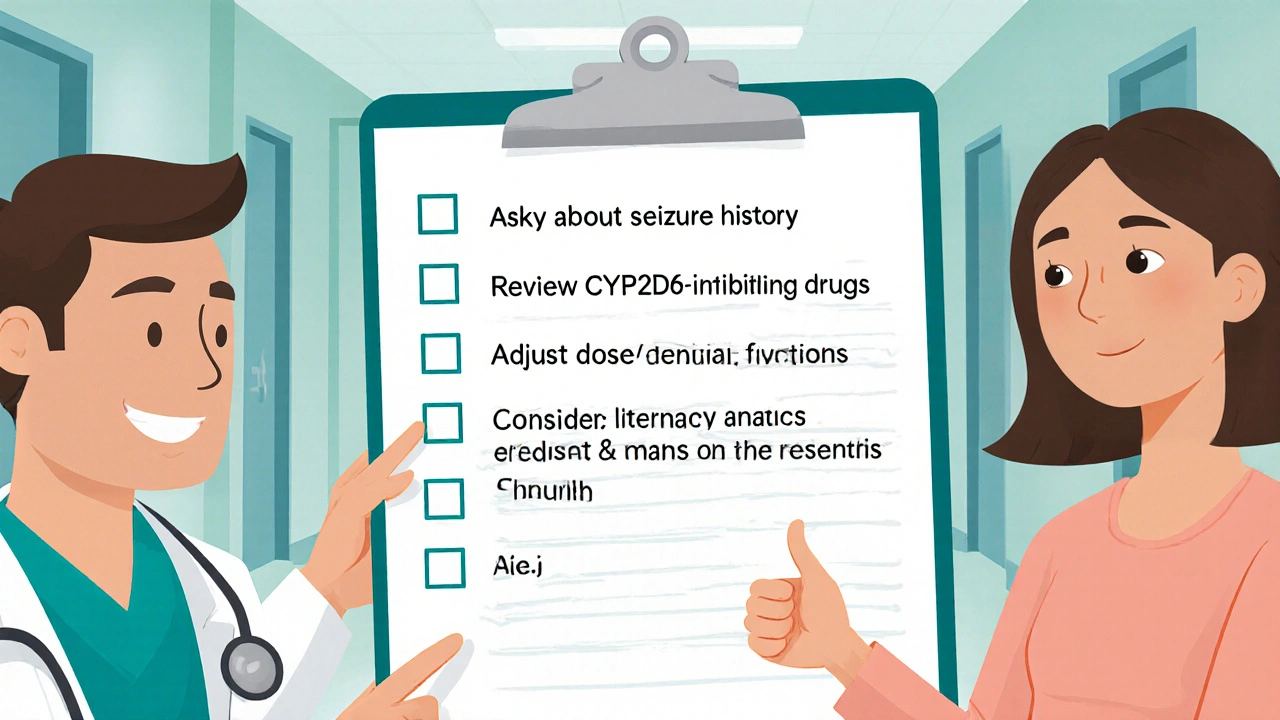

Quick Checklist for Clinicians

- Ask about any history of seizures or epilepsy.

- Review current meds for CYP2D6 inhibitors or other seizure‑threshold‑lowering drugs.

- Adjust maximum daily dose to 300 mg for patients ≥65 years or with eGFR < 60 mL/min.

- Consider alternative analgesics (acetaminophen, NSAIDs) when risk factors are present.

- Document dose changes and educate patients on seizure warning signs.

Bottom Line

Tramadol’s seizure risk isn’t a rare side effect - it’s a predictable outcome when certain factors line up. By screening for seizure history, avoiding CYP2D6‑inhibiting antidepressants, respecting age‑adjusted dosing, and staying vigilant for high‑dose misuse, clinicians can dramatically cut the number of preventable seizures.

What dose of tramadol is considered safe for older adults?

The FDA recommends a maximum of 300 mg per day for adults 65 years and older, and a 30% dose reduction when renal function (creatinine clearance) falls between 30-60 mL/min.

Can a patient with well‑controlled epilepsy safely take tramadol?

Even with controlled epilepsy, tramadol raises the odds of a breakthrough seizure by nearly four‑fold. Most guidelines advise avoiding tramadol or using it only after a specialist’s risk‑benefit assessment.

Which antidepressants are safest to combine with tramadol?

Non‑CYP2D6 inhibitors such as citalopram, escitalopram, or sertraline (at low doses) carry a lower interaction risk. Always check the specific metabolic profile before co‑prescribing.

How quickly do tramadol‑induced seizures typically appear?

Most seizures occur within the first six hours after ingestion, with an average onset of about 2.5 hours.

Is pharmacogenetic testing for CYP2D6 worth ordering before prescribing tramadol?

If the patient is elderly, has renal impairment, or will be on CYP2D6‑inhibiting drugs, testing can identify poor metabolizers who are at higher seizure risk and help guide safer dosing or alternative therapy.

10 Responses

Hey folks! 😊 It’s super important to check a patient’s seizure history before reaching for tramadol – a quick question on the intake form can save a lot of trouble. Also, keep an eye on any meds that hit CYP2D6; a simple med‑review often uncovers hidden risks. For older adults, dropping the dose to 300 mg or less is a good safety net. And remember, patient education about seizure warning signs is a win‑win for everyone. 🌟

Absolutely, those little screening steps can feel like extra paperwork, but they’re really a lifeline for patients who might otherwise be blindsided. I’ve seen a few cases where a simple “any history of seizures?” question changed the whole treatment plan. Thanks for laying it out so clearly! 💖

Tramadol’s dual action is a double‑edged sword: pain relief on one side, seizure potential on the other. The dose‑response curve is pretty linear, so staying under recommended limits matters. Elderly patients benefit from both dose reduction and renal function checks. Avoiding CYP2D6 inhibitors removes another layer of risk. Overall, a thoughtful prescription strategy pays dividends.

What if the “official” guidelines are just a smokescreen? They love to push tramadol because it’s cheap and easy to get, while hiding the seizure danger behind fine print. You’re told to check for CYP2D6 drugs, but who really monitors that in a busy clinic? It feels like a setup to keep us dependent on pharma’s safe‑harbor drugs.

Isn’t it fascinating how a molecule designed to ease pain can also tip the brain’s balance? When we look at the stats – 58% of overdoses leading to seizures – it’s a stark reminder that pharmacology is a dance between benefit and harm. I beleive that each patient’s story should guide the script, not just a checklist. Even a small oversight can turn a simple prescription into a life‑changing event.

Oh, sure, because prescribing a potent opioid is as harmless as a cup of tea. 🙄

From a practical standpoint, the key steps are: first, verify any prior seizure activity; second, run a quick drug interaction check for CYP2D6 inhibitors; third, adjust the dose based on age and renal function. For patients over 65, aim for a maximum of 300 mg per day, and reduce further if eGFR falls below 60 mL/min. If a patient is on fluoxetine or amitriptyline, consider switching to citalopram to avoid the metabolic bottleneck. Monitoring plasma levels isn’t reliable for seizure prediction, so rely on reported dose and clinical observation. Document all decisions in the chart for medico‑legal safety.

Looks like some of us still need a basic pharmacology refresher. 🙈 The evidence is crystal clear – avoid tramadol in high‑risk groups or pick a safer analgesic. A little diligence goes a long way, and it saves everyone from unnecessary ER visits. 🚑

The interplay between tramadol’s opioid activity and its serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibition creates a perfect storm for seizure susceptibility that cannot be ignored.

First, any clinician who prescribes tramadol without a thorough seizure history is basically gambling with the patient’s neural stability.

Second, the drug’s metabolism via CYP2D6 means that co‑administration with inhibitors such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, or amitriptyline doesn’t just raise plasma levels – it shifts the balance toward the parent compound that is more epileptogenic.

Third, age and renal function are not optional variables; they are fundamental determinants of how much tramadol actually stays in the system.

The FDA’s own labeling caps the dose at 300 mg for those over 65 and demands a 30 % reduction for creatinine clearance between 30–60 mL/min, yet many prescribers ignore these numbers.

When you look at the data from the 2019 Babahajian study, the odds ratio of 3.71 for seizure occurrence in patients with prior epilepsy is a wake‑up call.

Moreover, the 2023 Wei et al. analysis of over 70,000 nursing‑home residents shows a 9 % increase in seizure rates when tramadol is paired with CYP2D6 inhibitors, a figure that can’t be dismissed as statistical noise.

Adding to this, the pharmacogenetic research from Toronto points out that poor metabolizers experience a 3.2‑fold rise in tramadol levels after a standard dose, directly linking genotype to seizure risk.

In practical terms, the clinician should run a quick check: does the patient have a seizure disorder, are they on any CYP2D6‑inhibiting meds, are they older than 65, and do they have compromised renal function?

If the answer is yes to any of those, the prescription should either be halted or swapped for a non‑opioid analgesic such as acetaminophen or an NSAID, assuming no contraindications.

If tramadol is absolutely necessary, the dose must be titrated down to the lowest effective amount, with vigilant monitoring for any neurologic changes in the first six hours after administration.

Educating the patient about the hallmark signs of an impending seizure-auras, sudden visual changes, or a brief loss of awareness-is as crucial as the prescribing decision itself.

Documentation in the medical record should include the risk assessment, the rationale for choosing tramadol, and the specific monitoring plan; this protects both patient and provider.

Finally, remember that the risk is not theoretical; real‑world case reports, such as the Reddit user who suffered a first seizure after combining tramadol with sertraline, illustrate the tangible consequences.

By integrating these safeguards into everyday practice, we can dramatically reduce preventable tramadol‑induced seizures.

Ignoring them is simply irresponsible and runs counter to our duty of care.

They don't want you to see the full picture – the pharma lobby pushes tramadol while burying the seizure data in fine print. Even the "research" they cite is often funded by the same companies that profit from higher sales. Think about who benefits when patients end up in the ER and need more interventions.