Rising global temperatures, worsening air quality, and more frequent extreme weather events aren’t just headlines-they’re reshaping how our hearts work. If you’ve ever wondered whether the planet’s climate shift could make heart attacks more common, you’re in the right place. Below we break down the science, the numbers, and what you can do right now.

Key Takeaways

- Climate change amplifies traditional coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors like inflammation and oxidative stress.

- Air pollution and heat waves each add roughly a 5‑10% increase in heart‑attack risk, according to pooled data from 2020‑2024 cohorts.

- Older adults, people with pre‑existing hypertension, and low‑income communities face the steepest risk climbs.

- Mitigation starts with personal steps-indoor air filtration, staying hydrated during heat spikes, and regular exercise-but requires systemic policies on emissions and urban design.

- Research is moving toward real‑time climate‑health dashboards that can alert clinicians before a heat‑related cardiac event.

What is Coronary artery disease a condition where plaque builds up inside the coronary arteries, restricting blood flow to the heart muscle?

CAD is the leading cause of death worldwide. It develops when cholesterol‑rich fatty deposits (atherosclerotic plaques) harden, narrow, or rupture inside the vessels that feed the heart. Typical triggers include high LDL cholesterol, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and sedentary lifestyle.

While genetics set the baseline, environmental exposures often tip the balance. That’s where climate change enters the picture.

How climate change the long‑term shift in temperature, precipitation, and weather patterns driven by greenhouse‑gas emissions Affects Cardiovascular Health

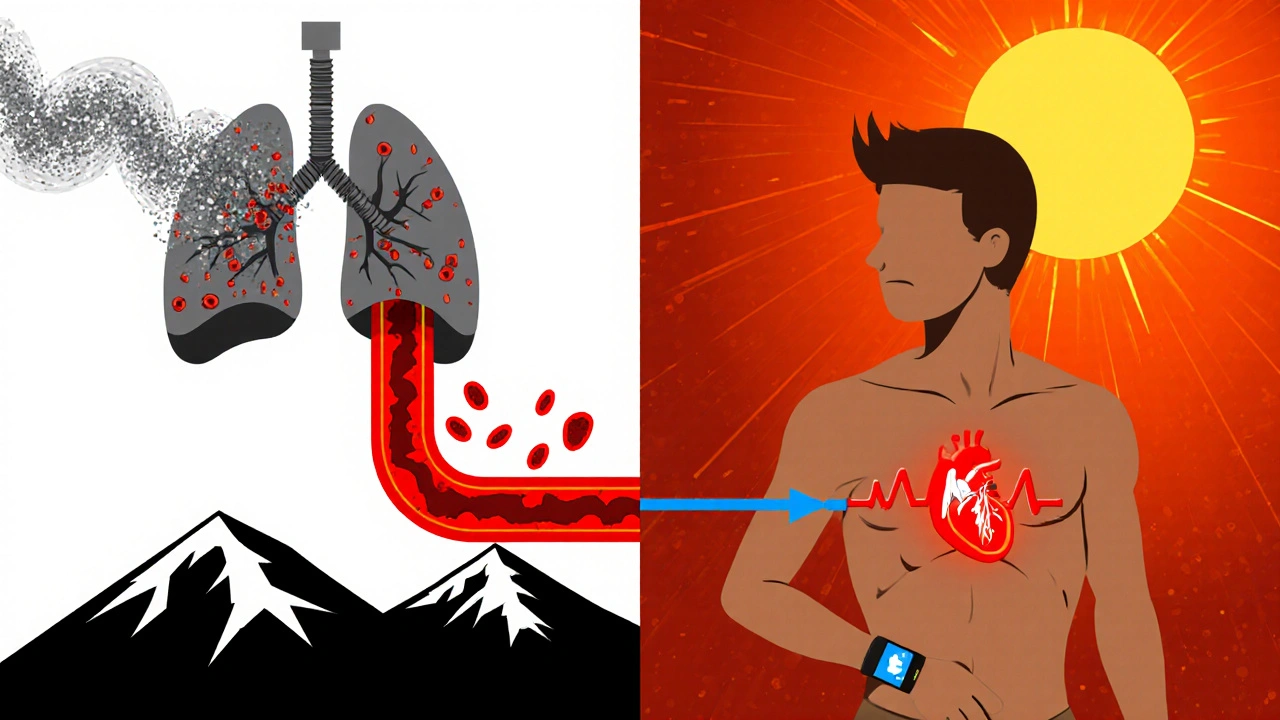

The link isn’t a simple cause‑and‑effect; it’s a cascade of physiological stressors:

- Air pollutants-especially fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone-stimulate systemic inflammation, which accelerates plaque formation.

- Rising temperatures raise core body heat, forcing the heart to pump faster to cool the skin; chronic heat exposure can raise blood pressure and increase arrhythmia risk.

- Extreme weather events (storms, floods) disrupt medication adherence, limit access to care, and trigger acute stress responses that raise catecholamine levels.

Each of these pathways converges on two main biological villains: inflammation and oxidative stress.

Specific Climate Drivers Linked to CAD

Below are the three climate‑related factors with the strongest evidence.

Air pollution the mixture of particles and gases released from vehicles, industry, and natural sources

PM2.5 can slip past lung defenses, enter the bloodstream, and trigger endothelial dysfunction-the first step in atherosclerosis. A 2023 meta‑analysis of 28 studies estimated that each 10µg/m³ increase in long‑term PM2.5 exposure adds a 12% higher risk of CAD events.

Heat waves periods of unusually high temperature lasting several days

During heat spikes, the heart works harder to dissipate heat, raising myocardial oxygen demand. For older adults, even a 2°C rise above average can boost heart‑attack rates by 7%.

Extreme weather disruptions

Storm‑related power outages force reliance on backup generators, which often emit higher levels of carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides. Moreover, displacement can interrupt antihypertensive medication regimens, a known CAD accelerator.

Evidence from Recent Studies (2020‑2024)

Large‑scale epidemiological work paints a clear picture:

- A U.S. cohort of 4.5million adults tracked from 2010‑2022 showed a 5% rise in myocardial infarction incidence per 1°C increase in average summer temperature.

- European data linking satellite‑derived PM2.5 concentrations with hospital admissions found that cities exceeding WHO air quality guidelines had 9% more CAD events than cleaner counterparts.

- In low‑income neighborhoods of Mumbai, the combination of high particulate levels and frequent heat waves correlated with a 14% earlier age of first‑time heart attack.

These numbers survive adjustment for smoking, diet, and socioeconomic status, underscoring a direct climate‑CAD connection.

Mitigation and Prevention Strategies

Addressing climate‑driven heart risk requires two tracks: personal defense and public‑policy action.

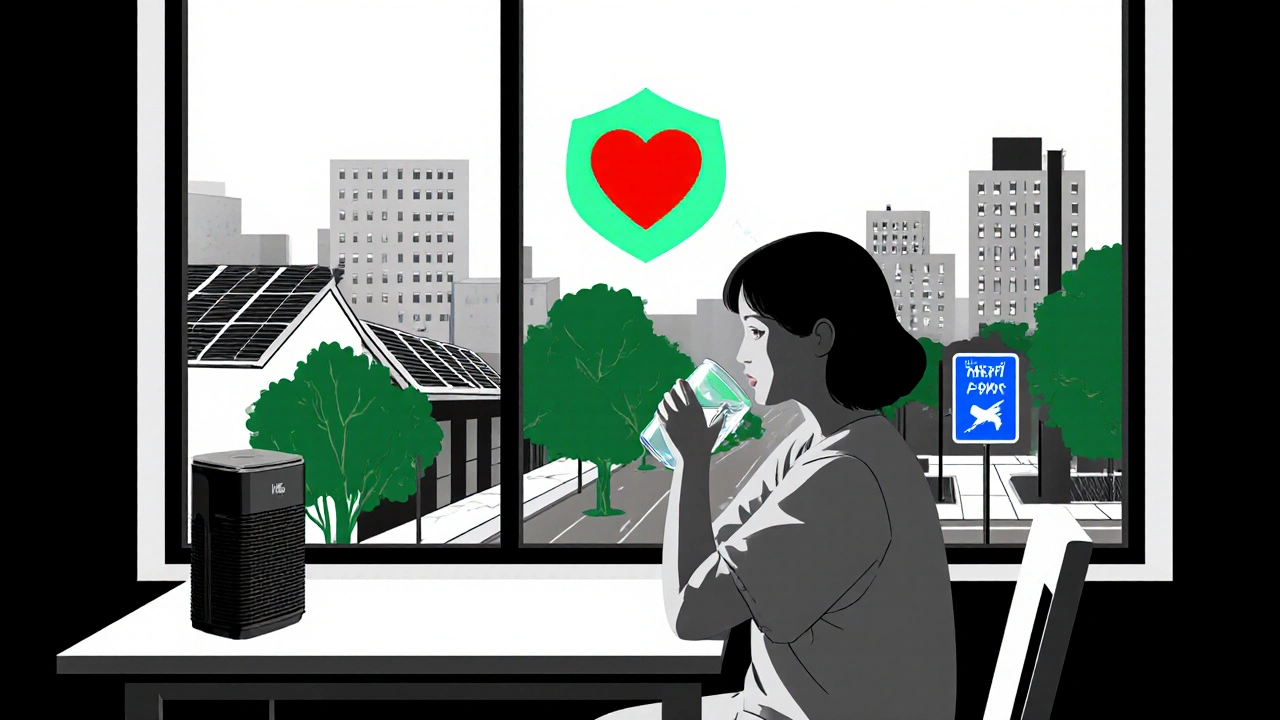

Personal steps you can take today

- Indoor air quality: Install HEPA filters, keep windows closed on high‑pollution days, and use indoor plants known to absorb VOCs.

- Stay hydrated and limit strenuous outdoor activity during heat alerts; wear lightweight, light‑colored clothing.

- Maintain a heart‑healthy diet rich in antioxidants (berries, leafy greens) to counter oxidative stress.

- Keep blood pressure and cholesterol under control-regular check‑ups become even more critical when the environment is hostile.

Policy levers that protect hearts at scale

- Stricter emissions standards for diesel trucks and power plants reduce PM2.5 exposure for entire cities.

- Urban greening projects (tree canopy expansion) cut ambient temperatures and filter particulates.

- Heat‑wave early‑warning systems that alert healthcare providers to schedule follow‑up calls for high‑risk patients.

- Investment in resilient health‑care infrastructure so hospitals stay operational during storms.

Future Outlook and Research Gaps

Scientists are now pairing climate models with cardiovascular risk calculators to predict where the next surge in CAD cases will hit. Real‑time wearable data (heart‑rate variability, skin temperature) could feed into community‑level alerts, helping doctors preempt heat‑induced cardiac events.

Key gaps remain:

- Longitudinal data from low‑income nations where climate impact is greatest.

- Understanding how combined exposures-pollution plus heat-interact at the molecular level.

- Evaluating effectiveness of city‑wide cooling centers on CAD outcomes.

Closing these gaps will sharpen both medical guidance and climate policy.

Comparison of Climate‑Related Risk Factors vs. Traditional CAD Risks

| Risk Factor | Typical Relative Risk | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 2.0× | Endothelial damage, oxidative stress |

| High LDL cholesterol | 1.8× | Plaque buildup |

| Hypertension | 1.5× | Arterial wall stress |

| PM2.5 exposure (10µg/m³) | 1.12× | Systemic inflammation |

| Heat‑wave days (>2°C above norm) | 1.07× per day | Increased cardiac workload |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can short‑term exposure to smog trigger a heart attack?

Yes. Studies show that a single day of high particulate matter can raise the odds of an acute coronary event by about 2‑3%, especially in people with existing plaque.

Do heat‑stroke protocols help prevent heart attacks?

Heat‑stroke treatments that lower core temperature quickly also reduce cardiac strain. Early hydration and cooling can cut the surge in heart‑attack admissions seen during heat waves by up to 40% in pilot programs.

Should I get a special heart‑health check if I live in a polluted city?

Annual cardiovascular screening is advisable for anyone exposed to high air‑pollution levels. Ask your doctor about measuring inflammatory markers like C‑reactive protein, which can flag early climate‑related risk.

Are there medications that offset climate‑driven heart risk?

Statins and low‑dose aspirin still work, but they don’t address the underlying inflammatory surge caused by pollutants. Antioxidant‑rich diets and, where appropriate, anti‑inflammatory drugs are being studied as adjuncts.

How can cities reduce climate‑related CAD risk?

Investing in clean public transport, expanding green spaces, enforcing emissions caps, and creating heat‑alert health services are proven strategies that lower community‑wide heart‑attack rates.

Next Steps for Readers

1. Check local air‑quality forecasts and limit outdoor exertion on poor‑quality days.

2. Install a HEPA filter in your bedroom and living area.

3. Keep a list of your heart‑medications handy during power outages.

4. Discuss with your physician how climate exposure might affect your personal CAD risk profile.

5. Support policies that cut emissions and fund urban greening-your health and the planet’s health are tied together.

9 Responses

Wow, the link between climate change and heart attacks is blowing up like a ticking time bomb! The science is clear: rising temperatures and smog are turning our arteries into pressure cookers. It feels like the powers that be are hiding the real agenda while we sweat it out on the streets. Stay hydrated, grab a HEPA filter, and keep an eye on those heat alerts – your heart will thank you. Remember, knowledge is the first line of defense against the hidden threats lurking in the air.

I think it’s refreshing to see a balanced take on a complex issue. Climate change certainly adds pressure on top of traditional risk factors, but we also have tools to mitigate those effects. Simple habits like staying indoors on bad air‑quality days and staying hydrated during heat waves can make a measurable difference. At the same time, we shouldn’t ignore the bigger picture of policy and infrastructure that can protect entire communities. Let’s keep the conversation open and supportive.

Dude you gotta realize that the heat waves are basically cardio bootcamps for everyone out there no joke

Even if you think it’s just a weather thing it’s messing with your blood pressure and heart rhythm

And the smog? Yeah that tiny particle sneaks into your bloodstream and starts a party of inflammation

It would be naïve to assume that the observed increase in myocardial infarctions is merely a coincidental correlation. The data suggest a coordinated effort to conceal the health ramifications of unchecked emissions, orchestrated by stakeholders with vested interests in fossil fuels. By manipulating air‑quality reports, they effectively mute the warning signals that could spur regulatory action. Therefore, the medical community must demand transparency and hold accountable those who profit from environmental neglect. Only then can we hope to decouple climate pressures from cardiovascular outcomes.

Honestly, the whole “just eat more berries” advice sounds pretentious when whole cities are choking on diesel fumes. Simple solutions like better public transit would actually move the needle.

These climate‑heart links are just another excuse for the west to blame the rest.

You’ve got to call out the hypocrisy – we’re told to buy expensive filters while corporations dump pollutants unchecked. The data don’t lie: PM2.5 spikes line up with heart‑attack spikes. Ignoring this is not just negligent, it’s malicious. If you care about your community, push for stricter emissions standards now. Anything less is a betrayal of public health.

Esteemed colleagues, I would like to extend my gratitude for the thorough exposition on the intertwining of climatic variables and coronary pathology. It is evident that the incremental rise in ambient temperature imposes an additional hemodynamic burden, particularly upon the elderly and hypertensive cohorts. Moreover, the particulate matter, especially PM2.5, serves as a catalyst for systemic inflammation, thereby accelerating atherogenesis. The authors rightly underscore the necessity of personal mitigation strategies, such as the utilisation of HEPA filtration systems and vigilant hydration practices. Equally important, however, is the advocacy for robust municipal policies that curtail emissions and promote urban greening initiatives. In this context, I find it imperative to highlight the role of interdisciplinary collaboration between cardiologists, climatologists, and urban planners. Such synergy can facilitate the development of predictive models that integrate meteorological forecasts with cardiovascular risk calculators. The prospect of real‑time alerts, as mentioned, heralds a new era of preemptive clinical intervention. Nonetheless, there remains a paucity of longitudinal data from low‑income nations, where the climate‑health nexus may be most profound. I encourage future research efforts to incorporate diverse geographic datasets to enrich our understanding. Additionally, we must critically assess the efficacy of community cooling centers in mitigating acute cardiac events. It is not sufficient to merely construct these facilities; we must evaluate their impact rigorously. Finally, public education campaigns should be tailored to culturally specific contexts, ensuring that the messages resonate across disparate populations. By fostering health literacy, we empower individuals to make informed decisions amidst environmental stressors. In conclusion, the synthesis of environmental stewardship and cardiovascular health is not merely an academic exercise but a societal imperative. I commend the authors for illuminating this vital intersection and look forward to continued dialogue.

Building on the comprehensive analysis provided, I would like to emphasize that the burden of climate‑driven cardiac risk is disproportionately shouldered by marginalized communities who often lack access to preventive resources

It is therefore essential that healthcare systems adopt outreach programs that deliver heart‑health screenings in areas with poor air quality and frequent heat waves

These programs should be synchronized with local weather services to schedule mobile clinics during cooler periods or after extreme events

Moreover, patient education materials need to be culturally sensitive, reflecting linguistic diversity and socioeconomic realities

By integrating community health workers into these initiatives, we can bridge the gap between scientific insight and actionable care

Ultimately, the convergence of policy, clinical practice, and grassroots activism will be the keystone in mitigating the cardiovascular toll of climate change