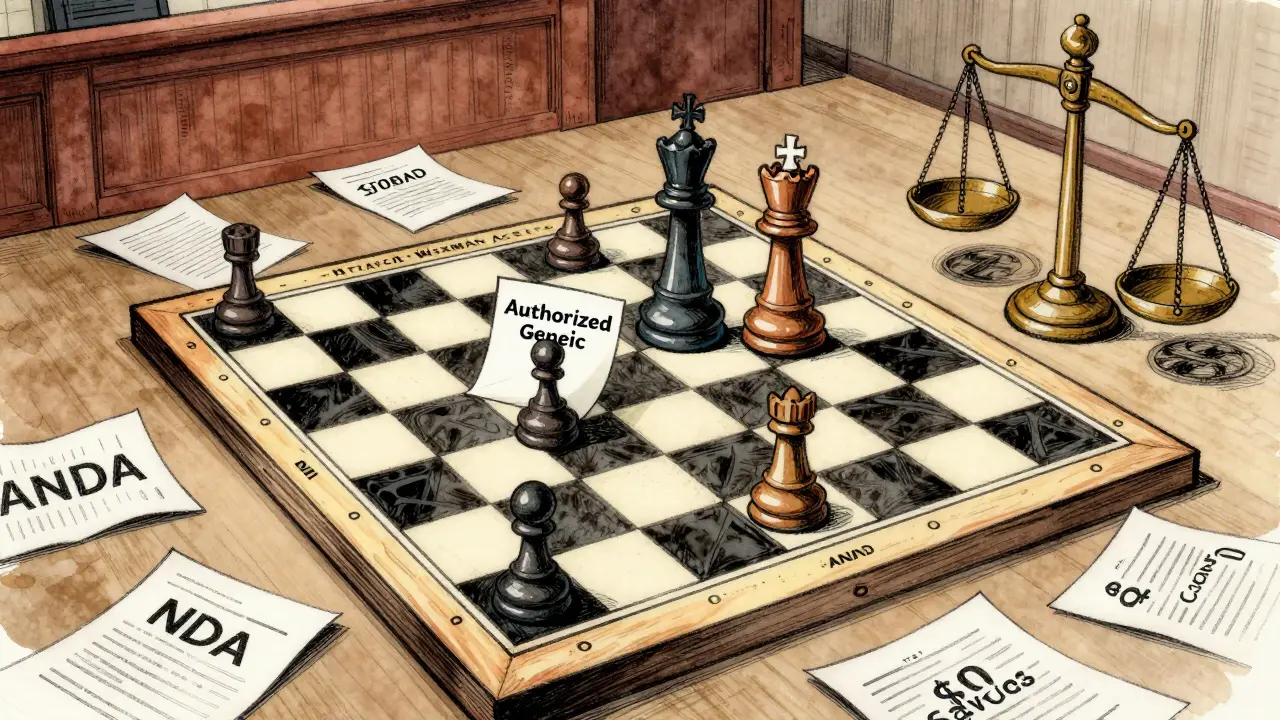

When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the race to sell the first generic version begins. But here’s the twist: the company that made the original drug might be the one launching the first generic - and they’re not breaking any rules. This isn’t a loophole. It’s a strategy. And it’s changing how prices drop, who profits, and who actually saves money.

What’s the difference between a first generic and an authorized generic?

A first generic is made by a company that challenges the brand’s patent and wins. They file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA, prove their version works the same as the brand drug, and if they’re the first to do it, they get 180 days of exclusive rights to sell it. During that time, no other generic can enter the market. That’s the reward under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 - a financial lifeline meant to encourage companies to take on the legal and scientific risk of patent fights.

An authorized generic is different. It’s made by the original brand company - or someone they’ve licensed - using the exact same formula, same factory, same packaging, just without the brand name. No ANDA needed. No bioequivalence studies. It’s the same pill, just labeled differently. And they can launch it anytime, even while the first generic is still enjoying its 180-day exclusivity.

That’s the key. The first generic has to wait months - sometimes years - to get FDA approval. The authorized generic? The brand company can flip the switch the moment the first generic hits the market.

Why does timing matter so much?

Imagine you’re Teva, and you’ve spent $8 million and three years fighting Pfizer’s patent on Lyrica (pregabalin). You finally win. The FDA approves your generic. You launch on July 1, 2019. You expect to capture 80% of the market. You’re planning your next acquisition.

Then, on the same day, Pfizer launches its own authorized generic through Greenstone LLC. Same pill. Same factory. Same price - or even lower.

Suddenly, instead of being the only game in town, you’re sharing the market. And not just sharing - you’re competing head-to-head with the very company you just defeated in court. Within weeks, Pfizer’s version takes 30% of sales. Teva’s market share drops from 80% to 50%. Revenue plummets. The 180-day exclusivity? It’s now a shared, diluted, far less profitable window.

This isn’t rare. Between 2010 and 2019, 73% of authorized generics launched within 90 days of the first generic’s approval. 41% launched on the exact same day. That’s not coincidence. That’s strategy.

How this breaks the original promise of the Hatch-Waxman Act

The Hatch-Waxman Act was built on a simple idea: reward the first generic company for taking the risk. That reward was supposed to be a monopoly - enough to make the legal battle worth it. That monopoly would then be broken by other generics, driving prices down further.

But when the brand company launches its own authorized generic, they turn that monopoly into a duopoly. The first generic still pays for the lawsuit, the FDA application, the manufacturing setup. But now they’re sharing the spoils with the original inventor.

The result? Prices don’t drop as much. Studies show that when an authorized generic enters during the exclusivity window, prices fall only 65-75% instead of the usual 80-90%. That might not sound like much, but on a $10,000-a-year drug, that’s thousands of dollars in lost savings per patient - every year.

And it’s not just patients. Medicare, Medicaid, insurers - everyone pays more than they should.

Who benefits? And who loses?

Brand-name companies win. They keep control of the market. They avoid the full price collapse. They get to keep the manufacturing line running. And they still get paid - just under a generic label.

Authorized generics also benefit the brand company’s shareholders. They don’t need to build new factories. They don’t need to hire new staff. They just repackage what they already make.

But the first generic company? They lose. Their investment - often $5-10 million - doesn’t pay off the way it was supposed to. Some companies have gone bankrupt after being undercut this way.

Patients? They get lower prices than before, sure. But not as low as they could have. And that gap adds up. RAND Corporation estimated that these maneuvers cost the U.S. healthcare system billions in avoided savings over the last decade.

Which drugs are most affected?

This isn’t happening with every drug. It’s concentrated in the big ones - the blockbusters with high sales volume and high profit margins.

Cardiovascular drugs lead the pack, making up 32% of cases. Think blood pressure meds, statins. Central nervous system drugs come next - antidepressants, anti-seizure meds, painkillers like Lyrica. Metabolic drugs like diabetes treatments are also common targets.

Current battlegrounds include Eliquis (apixaban) and Jardiance (empagliflozin). Both are multi-billion-dollar drugs. Both are on the verge of patent expiry. And both are already being watched closely by generic manufacturers who know what’s coming.

The FDA’s role - and why it’s not fixing this

The FDA approves both types of drugs. But they don’t regulate the timing. They don’t stop a brand company from launching an authorized generic the moment the first generic is approved. Their job is safety and efficacy - not market fairness.

And here’s the irony: the FDA’s own approval process is slow. The average ANDA review takes 10 months. But during the 2008-2012 backlog, some applications took over three years. Meanwhile, authorized generics can be launched in days.

That’s not a glitch. It’s a structural imbalance. The system was designed to reward innovation in generic entry. But it didn’t account for the brand companies having their own generic division.

What’s changing? And what’s next?

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 tried to address this. It explicitly says authorized generics don’t count as ‘generic competitors’ when Medicare negotiates drug prices. That’s a win for transparency - but not for competition.

Generic manufacturers are adapting. Leading companies now build dual strategies: one for the traditional first-generic play, and another for when the brand pulls the authorized generic card. Some are investing in faster FDA submissions. Others are focusing on less popular drugs where the brand company won’t bother fighting back.

By 2027, authorized generics could make up 25-30% of all generic prescriptions - up from 18% in 2022. That means more patients will see two generic versions side by side on the pharmacy shelf. One made by a challenger. One made by the original brand.

And the brand version? It might be cheaper. But it’s still the same company. And they’re still the ones controlling the price.

What should patients and prescribers know?

If you’re on a brand drug that’s going generic, don’t assume the first generic you see is the cheapest. Check the label. Is it made by the brand company? That’s an authorized generic. It’s not necessarily worse - but it’s not the independent competition the system was meant to create.

Ask your pharmacist: ‘Is this an authorized generic?’ They’ll know. If you’re paying out-of-pocket, compare prices. Sometimes the authorized generic is cheaper. Sometimes the first generic is. But you won’t know unless you ask.

And if you’re a doctor writing prescriptions, know that the lowest-priced generic isn’t always the most competitive option. Sometimes it’s the brand’s own product - and that’s not always in the patient’s best long-term interest.

There’s no villain here. No fraud. Just a system that was designed for one kind of competition - and now faces another.

Can a brand company legally launch an authorized generic while the first generic has exclusivity?

Yes. The Hatch-Waxman Act gives the first generic 180 days of exclusivity, but it doesn’t prevent the brand company from selling its own version under a generic label. Authorized generics don’t require an ANDA, so they can enter the market at any time - even on the same day the first generic launches. This is legal, though it’s widely seen as undermining the spirit of the law.

Are authorized generics the same as the brand-name drug?

Yes. Authorized generics are identical to the brand-name drug in active ingredients, dosage, strength, route of administration, and manufacturing facility. The only difference is the label - no brand name, no marketing. They’re not a copy. They’re the real thing, just sold under a generic name.

Why don’t all generic companies make authorized generics?

Because they can’t. Only the brand company - or someone they authorize - can make an authorized generic. It requires access to the original New Drug Application (NDA) and manufacturing setup. Independent generic companies don’t have that access. They have to go through the full ANDA process, which takes years and costs millions.

Do authorized generics lower drug prices?

They do - but not as much as independent generics. When only the first generic enters, prices drop 80-90%. When an authorized generic joins during the exclusivity window, prices drop only 65-75%. That’s because the brand company still controls pricing, and they’re not trying to undercut themselves - they’re trying to capture market share without letting the price collapse.

Is the FDA trying to stop authorized generics?

No. The FDA approves authorized generics because they meet safety and efficacy standards. Their role is not to regulate market competition - that’s up to the FTC and Congress. The FDA has no authority to delay or block an authorized generic launch, even if it undermines the first generic’s exclusivity.

12 Responses

The system was designed to help patients get affordable medicine, not to let big pharma play chess with their own patents. This isn't innovation-it’s exploitation dressed up as capitalism.

Man, I didn’t even know this was a thing. I just grab the cheapest pill off the shelf. Turns out the ‘generic’ I’ve been taking might be made by the same company that charged me $800 a bottle last year. That’s wild.

In India, we call this ‘pharma colonialism’-the same drug, same factory, same active ingredient, but now you’re paying for a label change while the original brand quietly pockets the difference. It’s not just unethical, it’s a global pattern. The West preaches competition but builds monopolies with legal loopholes. We see it in insulin, in HIV meds, in oncology drugs. The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to break chains, not forge new ones.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t a market failure-it’s a moral failure. The United States spends more on healthcare than any nation on earth, yet we’ve turned the most basic human need-medicine-into a rigged game where the house always wins. The FDA doesn’t regulate fairness because fairness isn’t profitable. And we wonder why people lose trust in institutions.

Actually, this is the free market working perfectly. Why should a company that invented the drug get punished for being efficient? If they can make it cheaper and faster, that’s capitalism. The first generic should’ve moved quicker. Blame their incompetence, not the system.

They’re not just launching generics-they’re sabotaging the competition before it even breathes. This is corporate warfare with FDA approval. And the worst part? The public thinks they’re saving money. They’re not. They’re just being fed the same pill with a different name and told to be grateful.

It’s not merely a legal quirk-it’s a philosophical collapse. The notion that ‘efficiency’ justifies the erosion of competitive incentives reveals a society that has confused profit with progress. When the innovator becomes the monopolist under a new label, we’ve abandoned the very idea of meritocracy. This isn’t capitalism. It’s feudalism with a pharmacy receipt.

And yet… people still don’t get it. They think ‘generic’ means ‘independent.’ It doesn’t. It means ‘brand-owned.’ They’re being sold a lie, and they’re too lazy to check the manufacturer’s name on the bottle. This is why America is falling apart-nobody reads the fine print anymore.

It is imperative to recognize that the structural design of the pharmaceutical regulatory framework has not evolved in tandem with corporate strategic behavior. The absence of statutory provisions governing the temporal alignment of authorized generic entry relative to first-generic exclusivity constitutes a regulatory gap of significant public health consequence. Stakeholders must advocate for legislative amendment to preserve the integrity of the Hatch-Waxman Act’s foundational intent.

Here’s what you can do: always ask your pharmacist if it’s an authorized generic. If it is, ask why it’s priced the way it is. Push back. Demand transparency. Your health is worth fighting for-even if it’s just one pill at a time.

It is a matter of public record that the United States Food and Drug Administration, while ensuring therapeutic equivalence, does not possess jurisdiction over market-entry timing. Consequently, the proliferation of authorized generics is not a regulatory failure, but a consequence of legislative inaction by the United States Congress, which has failed to update the Hatch-Waxman Act to reflect modern pharmaceutical business models. The solution lies in legislative reform-not blame.

This is why we can't have nice things.