Imagine trying to tell the difference between a ripe tomato and a green pepper, or spotting a red warning light on a dashboard - but the colors all look the same. For about 8% of men and less than 0.5% of women worldwide, this isn’t imagination. It’s everyday life. Red-green color blindness isn’t a disease you catch - it’s something you’re born with, passed down through genes like eye color or height. And while it doesn’t affect how clearly you see, it changes how you experience color in ways most people never think about.

What Exactly Is Red-Green Color Blindness?

Red-green color blindness isn’t seeing in black and white. It’s not blindness at all. It’s a mismatch in how your eyes process red and green light. Your retina has three types of cone cells - each sensitive to different wavelengths of light: red, green, and blue. For most people, these work together to create the full rainbow of colors we see. But in red-green color blindness, one or both of the red or green cones don’t function properly.

There are four main types:

- Deuteranomaly - the most common. Green cones don’t work right. About 5% of men have this. Reds and greens look muddy, and some shades of orange and brown get mixed up.

- Protanomaly - red cones are faulty. Reds look darker, almost brownish. This affects about 1% of men.

- Deuteranopia - no working green cones. You see mostly yellows, blues, and grays. Reds and greens appear identical.

- Protanopia - no working red cones. You can’t tell red from black or dark green. This is rarer than deuteranopia.

Deuteranomaly is by far the most frequent. Many people with it don’t even know they have it until they take a test or someone points out they’ve been mixing up colors for years. It’s not a flaw in vision sharpness - it’s a flaw in color discrimination.

Why Is It More Common in Men?

The reason men are far more likely to have red-green color blindness comes down to chromosomes. The genes that make the red and green photopigments - called OPN1LW and OPN1MW - are located on the X chromosome. Men have one X and one Y chromosome. Women have two X chromosomes.

If a man inherits an X chromosome with a faulty color vision gene, he has no backup. His Y chromosome doesn’t carry these genes. So one bad copy means color blindness.

Women, on the other hand, have two X chromosomes. For them to be color blind, both X chromosomes must carry the faulty gene. That’s much less likely. Statistically, if 8% of men have it, you’d expect about 0.64% of women to have it (8% of 8%). But actual rates are even lower - around 0.5% - because of something called X-inactivation, where one X chromosome gets randomly turned off in each cell. Sometimes, the healthy copy still does enough work to keep color vision mostly normal.

This is why your grandfather might have been color blind, your dad isn’t, but your brother is. It’s not random - it’s genetics in action.

How Is It Passed Down?

Here’s how it works in families:

- A color blind man passes his faulty X chromosome to all his daughters - but not his sons. His sons get his Y chromosome, which doesn’t carry the gene.

- A daughter who inherits the faulty gene from her father becomes a carrier. She usually doesn’t have symptoms, but she can pass it to her children.

- If a carrier woman has a son, there’s a 50% chance he’ll be color blind.

- If a carrier woman has a daughter, there’s a 50% chance the daughter will be a carrier too.

So you can have a color blind grandfather, a normal father, and a color blind grandson. The gene skipped a generation - not because it disappeared, but because it was hidden in the mother.

This pattern is called X-linked recessive inheritance. It’s the same reason hemophilia and Duchenne muscular dystrophy are more common in boys. The gene is there - but it needs two copies to show up in girls, and only one in boys.

How Do We Know Someone Has It?

The most famous test is the Ishihara test - those colorful plates with dots forming numbers. If you see a 5, but someone else sees a 2, it’s a clue. But these tests aren’t perfect. Some people memorize the patterns. Others have mild forms that don’t show up on the plates.

More accurate tests now use computer screens to measure how well someone can distinguish between shades of red and green. These are used in clinical settings and for jobs where color discrimination matters - like pilots, electricians, or train operators.

And yes - people have been disqualified from careers because of it. One Reddit user shared he was turned down as a commercial pilot applicant despite having 20/20 vision. He could see the lights - but not the colors. That’s not about skill. It’s about safety standards.

But most people never get tested. They just learn to adapt.

What Does It Actually Feel Like?

People with red-green color blindness don’t see the world in grayscale. They see color - just differently.

One engineer on a color blindness forum said he once wired a circuit board and mixed up red and green wires. He didn’t realize until the device sparked. Now he labels everything.

Another person described how she struggled in school when teachers used red pens to mark errors on green worksheets. She couldn’t see the corrections.

Even something as simple as picking out matching clothes can be a challenge. A survey by Colour Blind Awareness found that 37% of people with red-green deficiency have felt embarrassed when wearing mismatched outfits. One woman said she now buys clothes in sets - same color, same pattern - just to avoid the stress.

But many also say it’s not a disability. It’s a difference. One graphic designer told me he started using contrast and texture instead of color to design websites. He became better at accessibility because he had to think differently.

Can It Be Fixed?

No cure exists. The genes are there. The cones are there. You can’t swap them out.

But there are tools.

EnChroma glasses - the most well-known - cost between $329 and $499. They don’t restore normal color vision. They filter out overlapping wavelengths so red and green signals become more distinct. Studies show about 80% of users report better color separation - especially in outdoor light. But they don’t work for everyone. People with total loss of red or green cones (dichromats) usually don’t benefit.

There are also free digital tools. Color Oracle simulates color blindness on your screen so designers can check if their websites are readable. Apple and Windows have built-in color filters that shift hues to make reds and greens stand out. Microsoft says over 2.3 million people have used their filter since 2015.

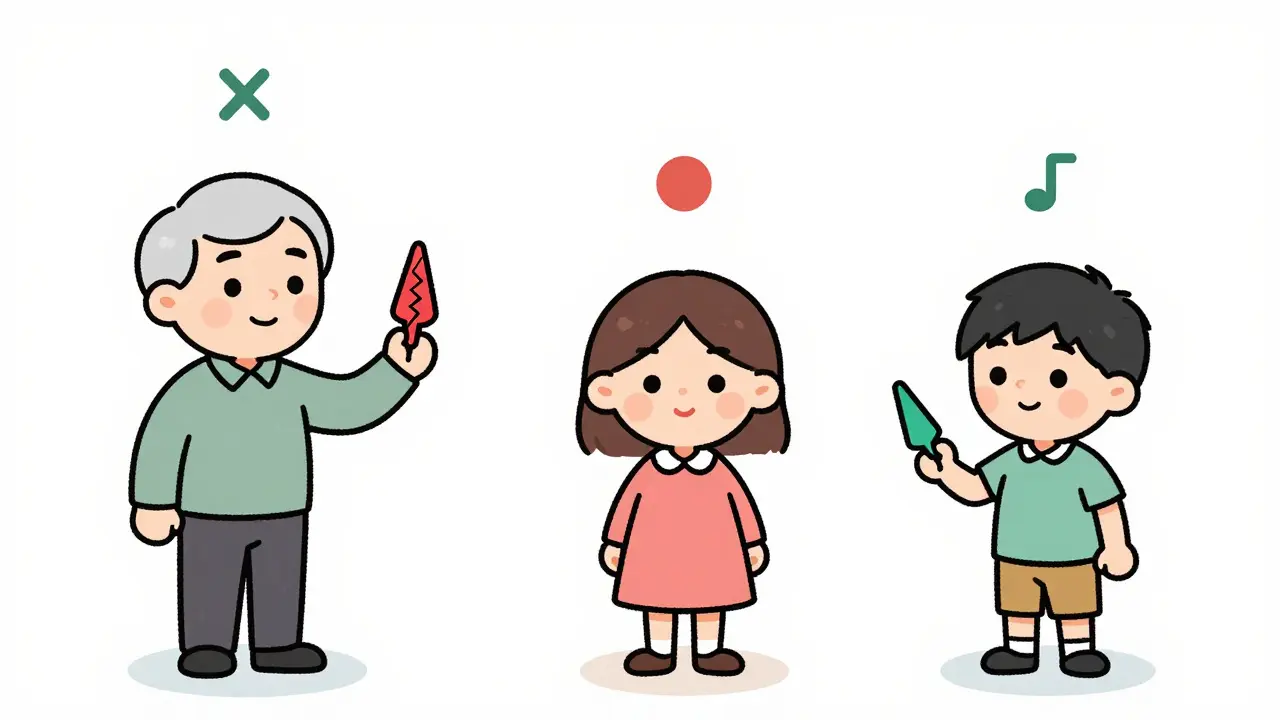

And then there’s ColorADD - a universal symbol system developed in Portugal. It uses simple shapes to represent colors: a triangle for red, a square for green, a circle for blue. It’s now used on public transit maps in 17 countries, in schoolbooks, and on medicine bottles.

These aren’t cures. They’re workarounds. And they’re getting better.

What’s Next for Color Vision Research?

Science is moving fast. In 2022, researchers at the University of Washington used gene therapy to give adult squirrel monkeys full red-green color vision for over two years. These monkeys were born color blind. After treatment, they could pick out red and green dots on a screen - something they never could before.

It’s not human-ready yet. But it’s proof that the brain can learn to use new color signals - even in adulthood. That’s huge. It means the problem isn’t just in the eyes. It’s also in the brain’s ability to interpret signals.

The National Eye Institute is funding this work. Their goal? Restore color vision in people, not just fix the symptoms.

Meanwhile, companies are improving lenses. EnChroma released a new version in 2023 specifically for deuteranomaly - the most common form - claiming a 30% improvement over older models.

And laws are catching up. The UK’s Equality Act 2010 recognizes color blindness as a disability. Employers must make reasonable adjustments. Schools are required to use patterns, not just colors, in teaching materials. The EU’s Accessibility Act forces public websites to meet color contrast standards.

It’s not about fixing people. It’s about fixing the world around them.

What Should You Do If You Think You’re Color Blind?

If you’ve always struggled with color-coded charts, traffic lights in fog, or matching socks - get tested. It’s easy. Many optometrists offer free screening.

Don’t assume it’s just “bad eyesight.” It’s not. It’s a specific, inherited condition. Knowing helps you adapt.

Use tools. Turn on color filters on your phone. Install the Colorblindifier plugin if you design graphics. Ask for labeled wires or patterns in school or work. Tell your friends and coworkers. Most people have never thought about it - until someone explains it.

And if you’re a parent and your son is color blind - don’t panic. He’ll be fine. He’ll learn to navigate the world. He might even become better at seeing contrast, texture, and structure than most people. He just sees red and green a little differently.

Color blindness isn’t a barrier. It’s a perspective.

Can color blindness get worse with age?

No. Red-green color blindness is genetic and doesn’t change over time. Unlike age-related vision loss, the cone cells don’t deteriorate. What you’re born with is what you’ll have for life. But other eye conditions like cataracts or macular degeneration can make color perception worse - and those are separate issues.

Can women be color blind?

Yes, but it’s rare. A woman needs to inherit the faulty gene from both her father and her mother. Since only about 8% of men are affected, and only half of women carry the gene, the chance of a woman having two copies is very low - around 0.5%. Most women who carry the gene don’t show symptoms, but they can pass it to their children.

Are there jobs you can’t do if you’re color blind?

Some, yes. Pilots, electricians, firefighters, and certain military roles require accurate color discrimination for safety. But many of these rules are outdated. In the UK and EU, employers must make reasonable accommodations - like using labels instead of color codes. You can still be a doctor, lawyer, teacher, or programmer. Most careers don’t require perfect color vision.

Do color-correcting glasses really work?

They help some people - especially those with deuteranomaly or protanomaly - but not everyone. They don’t cure color blindness. They filter light to make reds and greens appear more distinct. Many users report better color separation in natural light, like outdoors or under daylight bulbs. But they don’t help much under artificial lighting, and they don’t work for people with total loss of red or green cones.

Is red-green color blindness the same as blue-yellow color blindness?

No. Blue-yellow color blindness is completely different. It’s caused by a gene on chromosome 7, not the X chromosome. It affects men and women equally and is extremely rare - about 1 in 10,000 people. It’s also less understood and harder to test for. Most people who say they’re color blind mean red-green deficiency. Blue-yellow is almost unheard of in everyday life.

10 Responses

It is truly remarkable how deeply embedded genetic mechanisms are in our daily experiences. The X-linked recessive inheritance pattern of red-green color blindness is not merely a biological curiosity-it is a quiet testament to the precision of evolution. I have encountered individuals in my professional life who navigate color-coded systems with astonishing adaptability, often developing compensatory strategies that surpass conventional solutions. Their resilience is not a flaw in perception but a refinement of cognition.

Let’s be real-this isn’t just about cones and chromosomes. It’s about design failure. The world was built for people who see red and green the way we do, and that’s arrogant. EnChroma glasses? Cute. But why aren’t public transit maps, electrical panels, and educational materials universally labeled with symbols like ColorADD? We’re not asking for magic-we’re asking for basic accessibility. If we can make websites WCAG compliant, we can make color a secondary cue, not the primary one. It’s not about fixing the person. It’s about fixing the damn system.

As an American woman raised in a family of engineers, I find it infuriating that people still treat this as a minor inconvenience. This isn’t ‘just a difference’-it’s a safety risk in critical infrastructure. I’ve seen pilots fail color vision tests and then lobby to be exempted. That’s not inclusion-that’s negligence. And don’t get me started on the ‘graphic designer who sees better contrast’ narrative. That’s just privilege disguised as empowerment. Color blindness doesn’t make you more creative-it makes you less safe in high-stakes environments. Standards exist for a reason.

I'm deuteranomaly and never knew until I was 28. My dad had it too. We just called it 'seeing things weird'.

Been color blind since birth and honestly? I’ve got a better sense of texture and contrast than most people. I can spot a fake leaf in a fake plant from 20 feet away. 😄 Also, EnChroma glasses? Total game changer for sunsets. Not magic, but damn if they don’t make the sky look like it’s on fire. Cheers to the folks designing ColorADD-finally someone’s thinking ahead. 🇦🇺

As someone who grew up in a multilingual household where color terms varied drastically across dialects, I find this topic deeply resonant. Language shapes perception, and color blindness adds another layer to that. In some cultures, the distinction between green and blue is linguistically nonexistent-yet people navigate it effortlessly. This isn’t a deficit. It’s a reminder that human perception is malleable, and our tools must reflect that adaptability. The real failure isn’t in the eye-it’s in the rigidity of our systems.

THIS IS WHY I HATE MODERN TECHNOLOGY. I TRIED TO USE A SMARTPHONE TO SCAN A QR CODE AND IT WAS RED ON GREEN AND I THOUGHT IT WAS BROKEN. MY MOM SAID I WAS JUST STUPID. NOW I KNOW IT’S NOT ME. I’M NOT STUPID. THE WORLD IS STUPID. WHY CAN’T THEY JUST USE NUMBERS? I HATE COLORS.

Okay but what if this is all a government experiment? Like… what if they’re using color blindness to control how we see propaganda? I read this one article that said the military has been testing color filters on soldiers since the 80s to make them ‘more obedient to red signals’. And now we’re all being forced to use these ‘accessibility tools’? Sounds like a trap. Who benefits? Big Pharma? Google? The EnChroma company? They’re making billions off our confusion.

Wrong. Blue-yellow is rarer, but not because of chromosomes. It’s autosomal. Stop misinforming.

So we’ve spent centuries designing a world for people who see red and green, then act surprised when the 8% of men who don’t… struggle? 😏 The real tragedy isn’t color blindness. It’s that we still think ‘fixing’ the person is better than fixing the world. Bravo, humanity. Another gold star for systemic laziness.