When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA make sure that’s true? The answer lies in bioequivalence studies-a rigorous, science-driven process that generic drug makers must pass before their product can hit the market.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

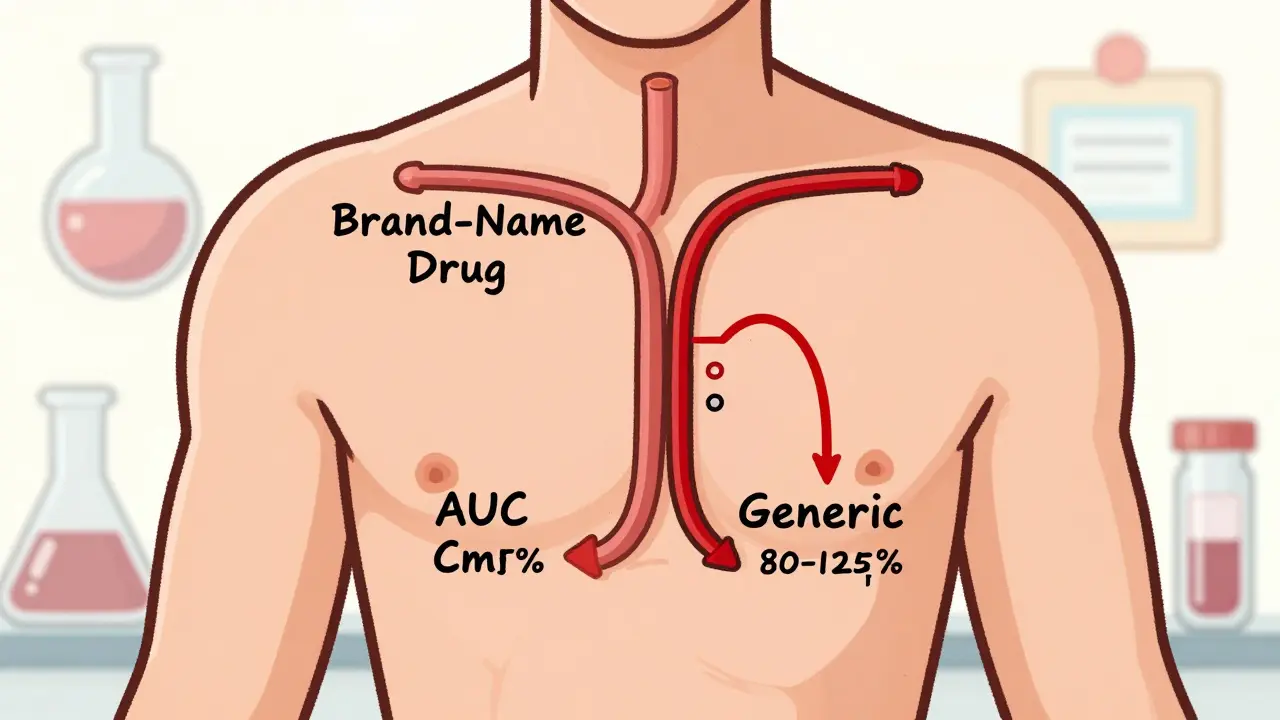

Bioequivalence isn’t about looking the same or tasting the same. It’s about whether the generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same speed as the original. The FDA defines it clearly: if two drugs are bioequivalent, there’s no significant difference in how fast and how much of the drug gets absorbed when taken under the same conditions.This isn’t just a technical detail. It’s the foundation of patient safety. If a generic drug is absorbed too slowly, it might not work. If it’s absorbed too fast, it could cause side effects. The goal? Make sure your body gets the same therapeutic effect, whether you’re taking the brand name or the generic.

The Two Requirements: Pharmaceutical and Bioequivalence

Before a generic drug can even start testing for bioequivalence, it has to meet one basic condition: pharmaceutical equivalence. That means the generic must have:- The same active ingredient

- The same dosage form (pill, injection, cream, etc.)

- The same strength

- The same route of administration (oral, topical, IV, etc.)

Once that’s confirmed, the real test begins: bioequivalence. This is where pharmacokinetic studies come in. These are clinical trials-usually done in healthy volunteers-that measure how the drug moves through the body. The two key numbers they look at are:

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): total drug exposure over time

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration): peak level in the blood

The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of these values between the generic and the brand-name drug falls between 80% and 125%. This is known as the 80/125 rule. It’s been the standard since 1992 and still holds today.

Why those numbers? Because they reflect a clinically acceptable range. If the generic delivers 85% to 115% of the brand’s exposure, it’s considered safe and effective. Outside that range, there’s too much uncertainty.

How the Studies Are Done

Most bioequivalence studies involve 24 to 36 healthy adults. They take the generic and the brand-name drug on separate occasions, often with a washout period in between. Blood samples are taken at regular intervals over 24 to 72 hours, depending on the drug’s half-life.Studies are usually done under fasting conditions-meaning no food for at least 8 hours before dosing. But if the drug’s absorption is affected by food, a second study is required under fed conditions. For example, drugs like itraconazole or griseofulvin need both tests because food changes how well they’re absorbed.

All labs must follow Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) rules. That means every sample is tracked, stored properly, and analyzed with validated methods. If the lab can’t prove its equipment and procedures are reliable, the FDA will reject the entire study.

When Bioequivalence Studies Can Be Skipped (Biowaivers)

Not every generic needs a full clinical trial. The FDA allows biowaivers for certain low-risk products where absorption isn’t a concern. These are based on the Q1-Q2-Q3 framework:- Q1: Same active and inactive ingredients

- Q2: Same dosage form and concentration

- Q3: Same pH, solubility, and dissolution profile

If all three match, the FDA may waive the in vivo study. This applies to:

- Oral solutions with identical ingredients

- Topical creams or ointments meant for local effect (like hydrocortisone for skin rashes)

- Ophthalmic and otic (ear) solutions

- Inhalant anesthetics

For topical products, the FDA may accept in vitro release testing (IVRT) and in vitro permeation testing (IVPT) instead of human trials. These tests measure how fast the drug comes out of the cream and how well it passes through skin layers-using artificial membranes and lab equipment.

Biowaivers save manufacturers months of time and up to $1 million per study. According to industry experts, using a biowaiver can cut development time by 6 to 12 months.

Special Cases: Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Some drugs have very little room for error. These are called narrow therapeutic index (NTID) drugs. Examples include warfarin (blood thinner), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), and phenytoin (anti-seizure). A small change in blood levels can cause serious harm-either under-dosing or toxicity.For these, the FDA tightens the bioequivalence window. Instead of 80-125%, the acceptable range is 90-111%. This means the generic must match the brand almost exactly. The FDA has issued specific guidances for each NTID, and manufacturers must follow them precisely.

Complex Drugs and New Tools

Not all drugs are simple pills. Topical creams, inhalers, nasal sprays, and injectable suspensions are harder to test. For these, traditional bioequivalence studies often don’t capture how the drug behaves in the body.The FDA is now using advanced tools like:

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling: Computer simulations that predict how a drug moves through the body based on its chemical properties

- Scale Average Bioequivalence (SABE): A method for highly variable drugs (like some antibiotics) where the 80-125% rule is too strict

These tools are still being validated, but they’re already being used in some ANDA submissions. The FDA expects to release draft guidances for 45 complex product types by mid-2024.

Why So Many ANDAs Get Rejected

Despite clear guidelines, nearly 6 out of 10 generic drug applications get rejected on the first try. The most common reasons?- Study design flaws (wrong number of participants, poor timing of blood draws)

- Weak analytical methods (lab can’t accurately measure drug levels)

- Missing documentation (incomplete records, unverified equipment logs)

- Not following the Product-Specific Guidance (PSG)

Companies that stick to the FDA’s 2,147 active PSGs have a 68% first-cycle approval rate. Those that don’t? Only 29%. The PSGs are detailed, sometimes hundreds of pages long, and cover everything from dissolution test conditions to acceptable excipients.

The FDA also runs a Domestic Generic Drug Manufacturing Pilot Program. If a company makes the active ingredient and runs the bioequivalence study in the U.S., they get a faster review. It’s not a guarantee, but it helps.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. but cost only 23% of what brand-name drugs do. That’s billions in savings every year. But none of that would be possible without bioequivalence studies.These studies aren’t just paperwork. They’re a public health safeguard. Every time someone switches from a brand to a generic, they’re trusting that the science behind it is solid. The FDA’s system-though complex-is designed to make sure that trust is never broken.

And it’s evolving. With new technologies, stricter rules for complex drugs, and more transparency through PSGs, the system is becoming more precise-not less. The goal? No compromise on safety. No shortcuts on science.

Do all generic drugs need bioequivalence studies?

No. Some generics qualify for a biowaiver if they meet strict criteria-same ingredients, same dosage form, and identical physicochemical properties as the brand. This applies mainly to oral solutions, topical products for local effect, and certain eye/ear drops. But for most pills and injectables, a full clinical bioequivalence study is required.

What happens if a generic drug fails bioequivalence testing?

If the 90% confidence interval for AUC or Cmax falls outside the 80-125% range, the FDA will not approve the product. The manufacturer must either redesign the formulation, run a new study, or submit additional data. Many companies go back to the lab and tweak their excipients or manufacturing process to fix absorption issues.

Are bioequivalence studies the same in the U.S. and Europe?

Yes, mostly. The FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) use nearly identical criteria-80-125% for most drugs, 90-111% for narrow therapeutic index drugs. Over 87% of their requirements are aligned, thanks to collaboration through the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). This means a study approved in the U.S. often meets European standards too.

How long does a bioequivalence study take to complete?

A typical in vivo study takes 6 to 9 months from planning to final report. This includes recruiting volunteers, conducting dosing sessions, analyzing blood samples, and compiling data. The actual clinical phase-where volunteers take the drug-is usually done in 1 to 2 months. But delays often come from lab analysis backlogs or regulatory review of methods.

Can a generic drug be approved without any human testing at all?

Yes, but only for very specific products. Biowaivers are granted for certain oral solutions, topical products, and inhaled anesthetics where absorption is predictable and local effects are the goal. For example, a hydrocortisone cream with the same ingredients and concentration as the brand can be approved without human trials. But for any drug meant to act systemically-like antibiotics or blood pressure pills-human testing is mandatory.

Why do bioequivalence studies cost so much?

Because they’re clinical trials. Costs range from $500,000 to over $2 million per study due to volunteer compensation, medical staff, lab equipment, data analysis, and regulatory compliance. Each blood sample must be handled under strict conditions, analyzed with validated methods, and backed by audit trails. Add in the need for GLP compliance and you’re looking at a high-stakes, low-margin process.

15 Responses

So I read this whole thing and honestly? I had no idea how much goes into generics. I always just assumed they were just copied pills. Turns out it’s way more science than I thought. Kinda cool.

Generic manufacturers are gaming the system and the FDA lets them get away with it. 80-125%? That’s a joke. I’ve had generics that made me sick and others that did nothing. This isn’t science it’s corporate laziness with a stamp of approval.

Man I love how detailed this is. I used to work in pharma logistics and I remember seeing those bioequivalence reports. The labs are insane-like, every blood sample has a barcode, a timestamp, and three people who signed off on it. And don’t even get me started on GLP compliance. One typo in the logbook and the whole thing gets tossed. It’s wild how much red tape keeps us safe.

Also the biowaiver thing? Genius. Why test 36 people when you can just prove the cream dissolves the same way? Saves so much time and money. Pharma companies should thank the FDA for that one.

It’s disgraceful that American regulators allow such loose standards. 80-125%? That’s a 45% window! In India we test with 90-110% for even basic drugs. And here, they let companies use labs overseas with questionable quality control? This isn’t healthcare-it’s a free-for-all for profit-driven corporations. The FDA is failing patients.

And don’t even get me started on how many ANDAs get rejected. It’s because the manufacturers don’t care. They hire third-world labs, cut corners on excipients, and still expect approval. This isn’t science. It’s fraud.

Why aren’t we demanding 100% equivalence? Why settle for 80%? If your life depends on it, you shouldn’t be gambling with numbers.

Let’s be real-bioequivalence studies are just a way for Big Pharma to keep generics expensive. The 80-125% rule? That’s a loophole. If the brand-name drug has a 10% variation in absorption due to manufacturing, why should the generic be held to a tighter standard? It’s not about safety-it’s about protecting profits.

And the PSGs? Hundreds of pages? That’s not guidance-that’s a barrier to entry. Only big companies can afford to navigate that. Small labs? Out of luck. So guess who’s left? The same corporations that make the originals.

This is so interesting!! I had no idea about the NTID window being 90-111%-that makes so much sense!! I’m so glad the FDA takes this seriously!! <3

It’s wild how much of this feels like alchemy. You’ve got this little pill, and somehow, through blood draws and math and lab equipment that costs more than a car, they figure out if it’s doing the same thing as the fancy version. It’s like magic, but with more spreadsheets.

And the fact that they use artificial skin to test creams? That’s next level. I picture some lab tech in a white coat gently rubbing synthetic epidermis like it’s a yoga mat. The dedication is absurd. In a good way.

As someone who has reviewed over 400 ANDAs, I can tell you the 80-125% rule is archaic. The statistical models used are outdated, the sample sizes are underpowered, and the reliance on AUC/Cmax ignores tissue distribution, metabolites, and pharmacodynamic endpoints. This isn’t bioequivalence-it’s a proxy for compliance. The FDA needs to adopt PBPK modeling as standard, not as a pilot. Until then, we’re all just guessing.

For anyone wondering why some generics work better than others-it’s not always the manufacturer. Sometimes it’s the excipients. Things like fillers, binders, or coating agents can change dissolution rates dramatically. That’s why the PSGs are so granular. One company uses corn starch, another uses pregelatinized starch-same active ingredient, totally different absorption. The FDA tracks this down to the particle size. It’s insane, but necessary.

I’ve been on levothyroxine for 12 years and switched generics three times. Two of them made me feel like a zombie. The third? Perfect. I didn’t know why-until I read this. Now I get it. The 90-111% range for NTIDs isn’t just bureaucracy-it’s lifesaving. Thank you for explaining this so clearly.

Oh so THAT’S why my generic Adderall felt like chewing on chalk last year. Classic. I thought it was just me being dramatic. Turns out, the manufacturer swapped out a filler and didn’t retest the dissolution profile. They got approved under a biowaiver because ‘technically’ it matched. But my brain knew. My brain always knows.

India produces 40% of the world’s generics. We have stricter standards than the FDA. Why does the U.S. accept lower quality? Because American consumers are lazy. They want cheap pills and don’t care if they’re safe. This isn’t innovation-it’s negligence.

When I see Americans complaining about drug prices, I laugh. You’re not paying for quality-you’re paying for a broken system that lets substandard products through because it’s cheaper. Shameful.

They’re lying. The FDA doesn’t test all generics. They rely on the manufacturers’ data. And those labs? Many are in China or India with no oversight. I know someone who worked at a lab that falsified results. They used the same blood samples for multiple trials. The FDA just rubber-stamps it. This is all a scam to keep people from suing the big pharma companies.

It’s fascinating, really. The entire system is built on trust-trust in the manufacturer, trust in the lab, trust in the FDA’s reviewers. And yet, with so many variables, so many human hands involved, how can we ever be certain? The numbers look clean on paper, but what if the sample was mishandled? What if the analyst was tired? What if the machine hadn’t been calibrated? The 80-125% rule… it’s not a guarantee. It’s a hope.

And don’t get me started on the fact that volunteers are paid to take these drugs. It’s not a clinical trial-it’s a transaction. We’re paying people to be guinea pigs. And then we act surprised when something goes wrong.

Here’s the real question: if bioequivalence is just about blood levels, then why do we assume that’s all that matters? What about epigenetic effects? What about gut microbiome interactions? What about long-term cumulative exposure? We’re measuring the tip of the iceberg and calling it science. The FDA is playing chess with a child’s board. They think if the pill gets into the bloodstream, it’s good. But the body isn’t a test tube. It’s a symphony. And we’re tuning it with a kazoo.