Autoimmune encephalitis isn’t something most people have heard of-until it hits close to home. It’s not a stroke, not a virus, not a typical brain infection. It’s when the body’s own immune system turns on the brain, attacking neurons and causing confusion, seizures, memory loss, and sometimes even catatonia. The good news? If caught early, it’s often treatable. The bad news? It’s easily missed. Symptoms start slowly, like a bad flu or a mood swing, and by the time doctors suspect it, precious time has passed.

What Are the Real Red Flags?

You might think of encephalitis as a feverish, confused patient with a stiff neck. That’s infectious encephalitis, usually from viruses like herpes. Autoimmune encephalitis looks different. It creeps in over days or weeks, not hours. The first signs? Often, they’re psychiatric. Someone becomes paranoid, aggressive, or withdrawn-like a personality change no one can explain. Or they start having unexplained seizures, especially if they’ve never had them before. Memory problems come fast: forgetting names, losing track of conversations, repeating questions. These aren’t normal forgetfulness. They’re sharp, sudden, and getting worse. Other red flags include:- Changes in heart rate or blood pressure-sudden spikes or drops without obvious cause

- Severe insomnia or sleeping 16 hours a day

- Faciobrachial dystonic seizures: brief, repetitive jerks in the face and arm, often happening dozens of times a day

- Low sodium levels in the blood (hyponatremia), causing nausea, confusion, or weakness

- Flu-like symptoms a week or two before neurological issues start: headache, fever, diarrhea

Which Antibodies Are Behind It?

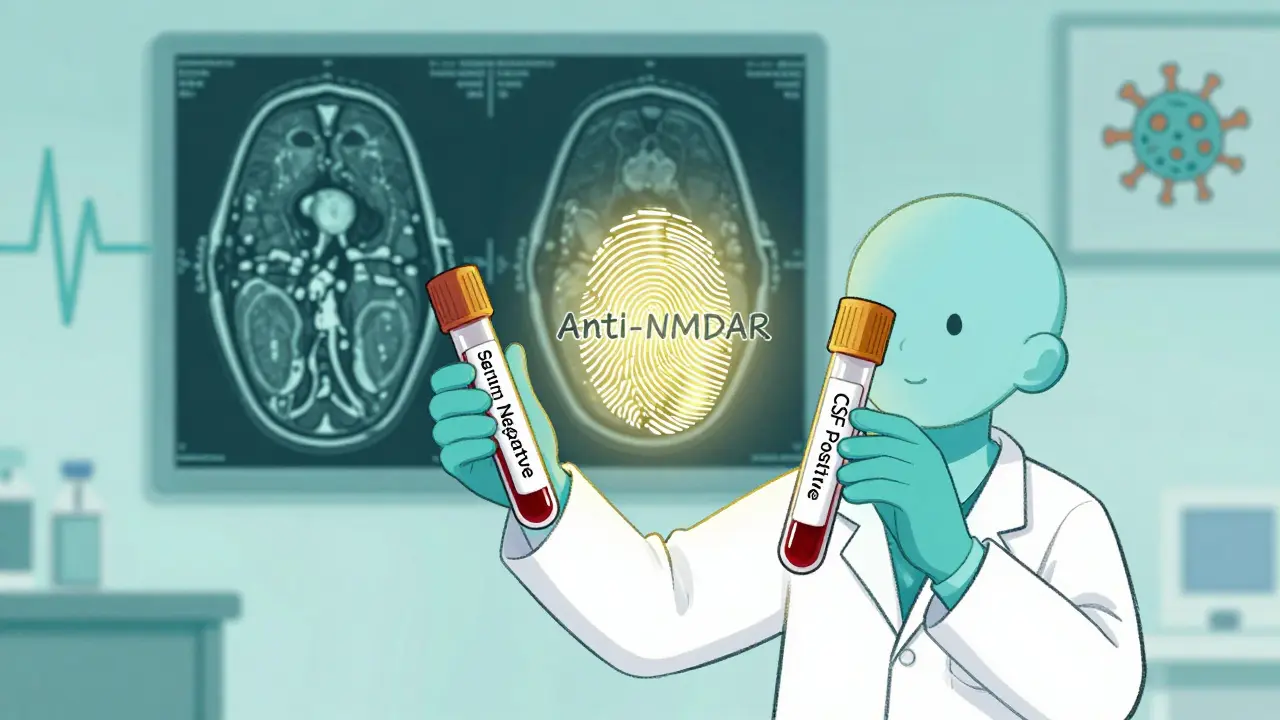

There are more than 20 known antibodies linked to autoimmune encephalitis. They’re like fingerprints-each one tells you something about the disease, who’s likely to get it, and what might be causing it. Anti-NMDAR is the most common, making up about 40% of cases. It hits young people, especially women in their 20s. Half of these cases are tied to ovarian teratomas-tumors that can be removed surgically. Once the tumor’s gone, the brain often starts healing. But even without a tumor, this type responds well to immunotherapy. Anti-LGI1 affects older men, mostly over 60. It’s known for those tiny, frequent facial and arm jerks (faciobrachial dystonic seizures). Almost two-thirds of patients have low sodium. Recovery is good-55% fully recover within two years-but it comes back in about one in three cases. Anti-GABABR is rare but dangerous. Half the people with this antibody have small cell lung cancer. If the cancer isn’t found and treated, the brain won’t recover. This one needs aggressive cancer screening. Less common antibodies include anti-CASPR2, anti-AMPAR, and anti-IgLON5. Each has its own pattern. Anti-GFAP, for example, often causes swelling in the spinal cord too. Testing for these isn’t simple. You need both blood and spinal fluid. CSF is more sensitive-up to 20% more likely to catch the antibody than blood alone. If you test only serum and it’s negative, don’t rule it out. Repeat the test with CSF.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single test. Diagnosis is a puzzle. Doctors look at symptoms, brain scans, spinal fluid, EEGs, and antibody results together. MRI scans can be normal in up to half of cases. When they do show something, it’s usually mild swelling in the temporal lobes-the memory centers. That’s called limbic encephalitis. It’s a big clue. Infectious encephalitis, by contrast, shows widespread damage in 89% of cases. EEGs often show slow brain waves, not the sharp spikes seen in viral infections. That’s a subtle but important difference. Spinal fluid analysis is critical. In autoimmune encephalitis, white blood cell counts are usually under 100 per microliter. In infections, they’re often in the hundreds or thousands. Protein levels are only mildly elevated. Oligoclonal bands? Usually absent. These details help rule out MS or infections. The 2023 diagnostic criteria from the International Autoimmune Encephalitis Consortium are the gold standard. They require:- Subacute onset (under 3 months)

- At least two of: new seizures, psychiatric symptoms, memory loss, altered consciousness, or movement disorders

- Exclusion of other causes

- Positive antibody test or typical MRI/CSF findings

What Are the Treatment Options?

Treatment is tiered. First-line, second-line, then third-line. The goal: shut down the immune attack fast. First-line therapy is usually high-dose steroids-1 gram of IV methylprednisolone daily for five days. It’s given in the hospital. About 68% of patients improve within a week or two. IV immunoglobulin (IVIg) is often given at the same time: 0.4 grams per kilogram of body weight daily for five days. It works in 60-70% of cases. But here’s the key: If there’s a tumor, remove it first. In anti-NMDAR encephalitis, 85% of patients improve after ovarian teratoma removal. In anti-GABABR, finding and treating lung cancer is life-saving. Screening must be thorough-pelvic ultrasound, CT chest/abdomen/pelvis. Repeat it in 4-6 months. 15% of tumors show up later. Second-line kicks in if first-line fails. That happens in 30-40% of cases. Rituximab (given weekly for four weeks) helps 55% of patients. Cyclophosphamide (monthly for six months) helps 48%. Tocilizumab, a newer drug, shows 52% response in resistant cases. Plasma exchange is used for the sickest patients-those in ICU with seizures or breathing problems. Five to seven sessions over two weeks can stabilize them fast. It clears antibodies out of the blood quickly. Timing is everything. Patients treated within 30 days of symptoms have a 78% chance of good recovery. If treatment is delayed beyond 45 days, that drops to 42%. Dr. Josep Dalmau, who discovered anti-NMDAR encephalitis, says: “Every day counts.” Don’t wait for antibody results. If the clinical picture fits, start treatment now.What Happens After Treatment?

Recovery isn’t instant. Even after the immune attack stops, the brain needs time to heal. About 55% of anti-LGI1 patients fully recover in two years. For anti-NMDAR, it’s 45%. But 40% of survivors have lasting problems. The most common long-term issues:- Cognitive: Memory loss, trouble focusing, slow thinking (32%)

- Psychiatric: Depression, anxiety, mood swings (28%)

- Seizures: Needing ongoing anti-seizure meds (22%)

9 Responses

This is wild-I had a cousin in Delhi who went from being super chill to screaming at mirrors and forgetting her own birthday. Doctors called it ‘stress’ for months. Then she had a seizure in the grocery store. Turned out to be anti-NMDAR. They found a teratoma. She’s back to teaching yoga now. If you’re seeing weird brain stuff + low sodium, don’t wait. Push harder.

The diagnostic criteria from the 2023 International Autoimmune Encephalitis Consortium are robust, particularly the requirement for subacute onset and exclusion of alternative etiologies. CSF oligoclonal band negativity is a critical differentiator from MS, and the sensitivity gap between serum and CSF antibody testing (~20%) underscores the necessity of lumbar puncture-even when MRI is unremarkable. Early immunotherapy initiation, prior to serological confirmation, aligns with the principle of therapeutic urgency in neuroimmunology.

so like… brain attacks itself. cool. next up: my liver files a restraining order. 🤡

but seriously-why is this not on every med school quiz? they’re out here diagnosing ‘depression’ while the brain’s literally being eaten by its own army. send help. or at least a neurologist.

WHAT?!?!? You’re telling me people are getting misdiagnosed with ‘anxiety’ while their neurons are being DESTROYED?!?!?!?! I’ve been screaming about this since 2020!! My sister had faciobrachial seizures and they put her on Xanax for SIX MONTHS!! WHY ISN’T THIS IN THE NEWS?!?!?!?!?!?!!??

Think about it-our immune system, this beautiful, ancient, hyper-vigilant guardian, evolved to kill pathogens… but now it’s turned its gaze inward, toward the very organ that makes us conscious, that lets us love, write poetry, feel grief. It’s not just a disease-it’s a betrayal from within. And yet, we treat it like a glitch in the software. We give steroids like they’re bandaids on a nuclear reactor. But maybe… maybe the real question isn’t how to stop the attack-but why the body decided to turn on itself in the first place. Is it environmental? Epigenetic? A silent war triggered by a virus we never knew we carried? The answer might lie not just in CSF, but in the soul of our biology.

Oh wow, another ‘you’ve been misdiagnosed for years’ post. How original. I’m sure the 17 neurologists who missed it were just too busy sipping lattes. Anyway, anti-LGI1? Cute. I’ve got a patient with anti-IgLON5 who slept 20 hours a day and dreamed in 4D. Yeah, I’m the real MVP.

Red flags? Antibodies? Treatment tiers? All well and good. But where’s the cost breakdown? Who pays for 7 plasma exchanges? Who covers the CT scans? This reads like a textbook written by someone who’s never had to file an insurance claim.

Actually, the GFAP blood biomarker thing? That’s huge. If it pans out, we could replace invasive LPs with a simple finger prick. Imagine a world where you get a ‘brain inflammation alert’ on your phone after a flu. I mean… we’ve got apps for everything else. Why not this? Also, melatonin for sleep? 3-5mg? That’s basically a sleep grenade. I’d just take a nap and hope for the best.

My uncle in Mumbai had this. They thought it was dengue at first. Then seizures. Then he forgot my name. We pushed for CSF testing-thank god we did. Anti-NMDAR. Tumor removed. Now he’s back to teaching math. 🙏 If you’re reading this and someone you love is acting ‘off’-don’t wait. Ask for antibodies. Ask for CSF. You might save them. ❤️