When doctors need to calm a rapid heart rhythm that originates above the ventricles, they often turn to Amiodarone. Amiodarone is a class III antiarrhythmic agent that works by prolonging the cardiac action potential and refractory period, mainly through potassium channel blockade. It also has beta‑blocking, calcium‑channel blocking and sodium‑channel effects, which makes it a “broad‑spectrum” drug for many arrhythmias.

What is Supraventricular Tachycardia?

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) refers to any tachyarrhythmia that starts above the ventricles, typically involving the atria or the atrioventricular node. Common sub‑types include atrioventricular nodal re‑entrant tachycardia (AVNRT), atrioventricular re‑entrant tachycardia (AVRT) and atrial tachycardia. Episodes can last seconds to hours, causing palpitations, dizziness, chest discomfort, or even heart failure if poorly controlled.

Why Consider Amiodarone for SVT?

Guidelines from the ACC/AHA (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association) place Amiodarone as a second‑line option when first‑line agents (beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin) fail or are contraindicated. Its multi‑channel actions give it the power to terminate refractory SVT episodes that don’t respond to more selective drugs.

Clinical Evidence of Efficacy

Multiple studies published between 2015 and 2023 have examined Amiodarone’s success rate in SVT conversion:

- A 2018 randomized trial of 212 patients with refractory AVNRT showed a 71% conversion rate within 10 minutes of IV bolus (150mg), compared with 48% for intravenous verapamil.

- A 2021 meta‑analysis of nine studies (total n=1,047) reported an overall acute conversion success of 68% for SVT, with a median time to conversion of 8minutes.

- Long‑term follow‑up in a 2022 cohort of 84 patients demonstrated a 39% recurrence rate at 12months, which is comparable to the 42% seen with beta blocker therapy.

These numbers suggest Amiodarone is at least as effective as traditional agents, especially when rapid control is needed.

How Amiodarone Works - Mechanistic Snapshot

Amiodarone’s antiarrhythmic profile is often summarized with the mnemonic “V‑K‑B‑S” (Ventricular, potassium, beta, sodium) but the same principles apply to supraventricular tissue:

- Potassium channel blockade - prolongs phase 3 repolarization, lengthening the QT interval and preventing premature atrial beats from re‑entering the circuit.

- Beta‑adrenergic inhibition - reduces sympathetic drive, lowering heart rate and atrial automaticity.

- Calcium channel inhibition - slows AV nodal conduction, useful in AV‑node‑dependent SVT.

- Sodium channel effect - stabilizes the myocardial cell membrane, limiting ectopic firing.

Because it touches all four pathways, Amiodarone can shut down SVT mechanisms that bypass a single‑target drug.

Dosage Forms and Administration

For acute SVT, the standard IV regimen is:

- Loading bolus: 150mg over 10minutes.

- If rhythm persists, a second bolus of 150mg may be given.

- Maintenance infusion: 1mg/min for 6hours, then 0.5mg/min for up to 24hours.

Switch to oral therapy once the patient is stable:

- Loading oral dose: 200mg three times daily for one week.

- Maintenance: 200mg daily (adjust based on response and toxicity monitoring).

Note: Amiodarone has a very long half‑life (up to 100days), so steady‑state levels take weeks to achieve.

Safety Profile - What to Watch For

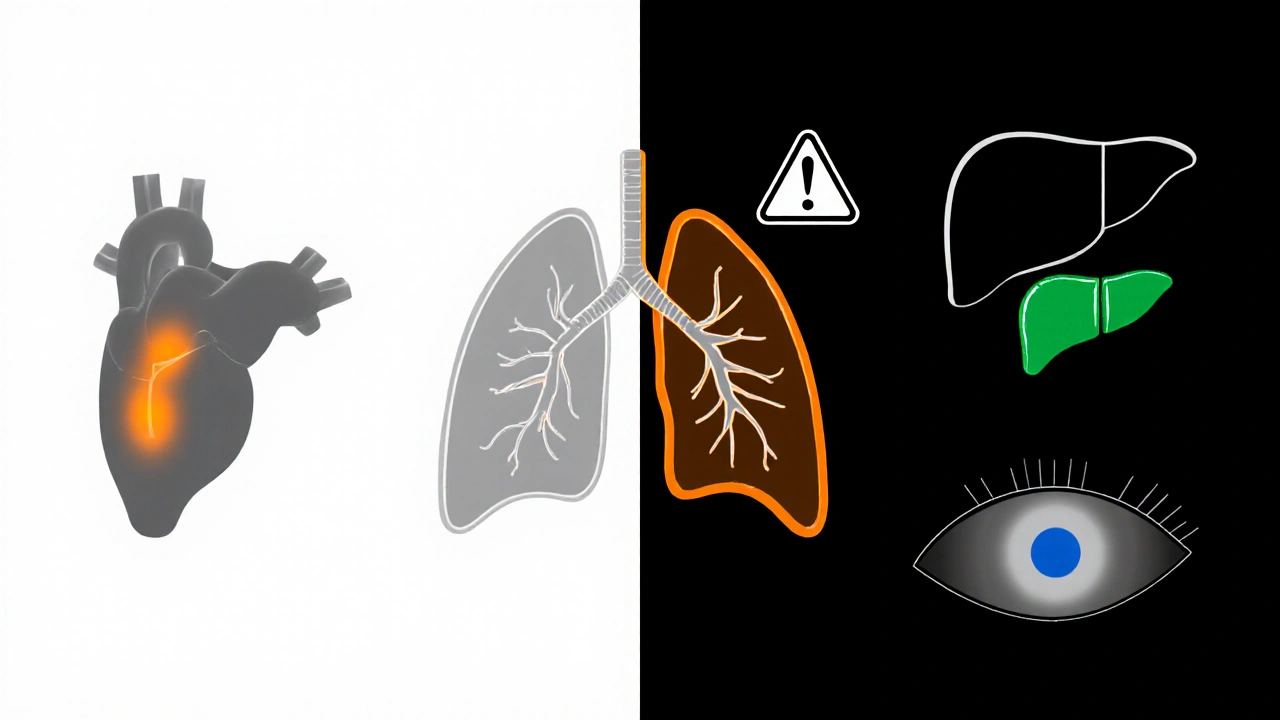

While Amiodarone is powerful, its side‑effect spectrum is broad. Key toxicities include:

- Thyroid toxicity - both hypothyroidism (≈20% of patients) and hyperthyroidism (≈5%). Baseline TSH and periodic monitoring are mandatory. \n

- Pulmonary toxicity - interstitial pneumonitis or fibrosis, occurring in 1‑5% of long‑term users; early cough or dyspnea should prompt imaging.

- Hepatotoxicity - elevated transaminases in up to 15%; liver function tests weekly for the first month, then monthly.

- Corneal micro‑deposits (seen in >90% on slit‑lamp exam, usually benign).

- Photosensitivity and skin discoloration.

Because Amiodarone prolongs the QT interval, clinicians must monitor ECG for torsades de pointes, especially when combined with other QT‑prolonging drugs.

Comparing Amiodarone to Other SVT Therapies

| Drug | Acute Conversion Rate | Time to Conversion | Major Side‑Effects | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone | 68‑71% | 8‑10minutes | Thyroid, pulmonary, hepatic toxicity; QT prolongation | Refractory SVT, contraindication to beta‑blocker |

| Beta blocker (e.g., metoprolol) | 55‑60% | 12‑15minutes | Bronchospasm, bradycardia, hypotension | First‑line in patients without asthma |

| Calcium channel blocker (verapamil) | 48‑55% | 10‑14minutes | Hypotension, constipation, AV block | Patients with asthma or contraindicated beta‑blocker |

| Digoxin | 30‑40% | 15‑20minutes | Arrhythmias, nausea, visual disturbances | Heart failure with SVT, elderly |

Amiodarone’s higher conversion rate and rapid effect make it attractive in emergency settings, but the long‑term toxicity profile pushes clinicians toward quicker‑acting, safer agents for routine cases.

Practical Tips for Clinicians

- Reserve IV Amiodarone for SVT that fails after at least one trial of a beta blocker or verapamil.

- Always obtain a baseline ECG, thyroid panel, liver enzymes, and chest X‑ray before the first dose.

- Monitor the QT interval continuously; stop the infusion if QTc exceeds 500ms.

- Educate patients about skin photosensitivity and the need for regular eye exams.

- Consider a lower maintenance dose (100‑200mg) in patients with borderline thyroid or hepatic function.

Future Directions

Research is exploring lipid‑nanoparticle delivery of Amiodarone to reduce systemic exposure, and early‑phase trials of selective potassium‑channel blockers aim to retain efficacy while sidestepping thyroid and pulmonary toxicity. Until those hit the market, Amiodarone remains a valuable second‑line weapon for hard‑to‑control SVT.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Amiodarone be used for chronic SVT management?

Yes, but only when other oral agents (beta blockers, calcium channel blockers) are ineffective or contraindicated. Chronic use requires close monitoring of thyroid, liver, and lung function because toxicity accumulates over weeks to months.

What is the recommended IV dose for an adult with acute SVT?

A 150mg bolus over 10minutes, repeat once if needed, followed by a maintenance infusion of 1mg/min for 6hours, then 0.5mg/min up to 24hours.

How often should thyroid function be checked during Amiodarone therapy?

Baseline TSH, then every 3months for the first year, and every 6months thereafter, or sooner if symptoms of hypo‑ or hyper‑thyroidism appear.

Is Amiodarone safe in patients with pre‑existing lung disease?

Caution is advised. Pulmonary toxicity risk rises in patients with COPD or interstitial lung disease. Baseline chest imaging and frequent symptom review are essential; many clinicians avoid Amiodarone in severe lung disease.

How does Amiodarone compare to catheter ablation for SVT?

Catheter ablation offers a curative solution with >95% success and minimal long‑term drug toxicity. Amiodarone is a pharmacologic bridge when ablation is unavailable, contraindicated, or the patient prefers a non‑invasive approach.

15 Responses

Amiodarone is a double‑edged sword that can rescue a patient in a frantic SVT episode.

Its ability to hit multiple ion channels gives clinicians a powerful tool when first‑line agents fail.

However, that same breadth of action is what fuels the long‑term toxicity that haunts many users.

Think of the thyroid as a delicate balance beam; once amiodarone tips it, you may spend months adjusting hormones.

The lungs, too, can become a silent battleground where interstitial changes creep in unnoticed.

On the bright side, the rapid conversion rates reported in recent trials mean you can restore sinus rhythm in under ten minutes for many patients.

That speed can mean the difference between a stable admission and a cascade of hemodynamic compromise.

It is essential, therefore, to pair the drug with a rigorous monitoring protocol from day one.

Baseline ECG, TSH, liver enzymes, and a chest X‑ray set the stage for safe administration.

After the bolus, keep a watchful eye on the QT interval; crossing the 500 ms threshold warrants immediate cessation.

If the patient tolerates the infusion, transition to an oral loading dose while continuing to check thyroid function every three months.

Remember that the half‑life stretches toward three months, so any side‑effect may linger long after the last pill.

In patients with pre‑existing pulmonary disease, weigh the risk‑benefit ratio heavily before pressing the button.

For younger individuals with fewer comorbidities, the risk profile may be acceptable when arrhythmia control is urgent.

Conversely, in a frail elderly patient, a beta‑blocker or calcium channel blocker may be a safer first strike.

Ultimately, the decision hinges on a shared conversation with the patient, acknowledging both the life‑saving potential and the long‑term vigilance required.

This drug is a nightmare for patients and doctors alike!

When you look at the data, the conversion numbers are impressive, especially for stubborn AVNRT cases.

The IV bolus does the trick fast, which can be a lifesaver in the ER.

Still, we can’t ignore the thyroid and lung warnings – they’re real and need monitoring.

Balancing rapid rhythm control with long‑term safety is the key challenge.

Sharing these pros and cons with patients helps them make an informed choice.

Agreed, the speed is a huge plus 😊

Just make sure you have the labs drawn before you hit that 150 mg bolus.

And keep the ECG handy – QT spikes can happen fast.

Overall, a solid option when the first line flops.

Philosophically, we are trading short‑term certainty for long‑term uncertainty.

Amiodarone’s power is undeniable, yet it casts a long shadow over thyroid health.

Patients must be prepared for a lifelong monitoring commitment.

The ethical balance lies in honest disclosure and shared decision‑making.

Otherwise, we risk undermining trust in our therapeutic judgments.

I hear you, and I’d add that the notion of “acceptable risk” evolves with each patient’s comorbid profile.

For a young athlete with a reversible SVT trigger, the rapid control may outweigh the thyroid risk, especially if baseline labs are normal.

Conversely, an older patient with borderline liver enzymes might be better served by a calcium channel blocker.

It’s also worth noting that the dose‑adjustment algorithm can be fine‑tuned; starting at 100 mg daily and titrating based on TSH trends is a pragmatic approach.

In practice, multi‑disciplinary rounds involving cardiology, endocrinology, and pharmacy often yield the safest pathway.

Ultimately, the decision rests on a nuanced risk‑benefit calculus that respects the individual’s values and health context.

Energy boost! Amiodarone can be the hero in an acute SVT storm.

Just remember to set up the monitoring plan before you start.

Teamwork makes the dream work.

Your enthusiasm is spot‑on.

Monitoring thyroid function every three months is a good baseline.

Also, scheduling a follow‑up chest X‑ray after a week can catch early pulmonary changes.

Balancing urgency with safety keeps everyone happy.

The manuscript makes several grammatical oversights; for instance, "150mg" should be rendered as "150 mg" for typographic consistency.

Furthermore, the phrase "Can be shut down" is colloquial; a more precise formulation would be "can be inhibited".

The dosing schedule would benefit from a tabular representation to enhance clarity.

Lastly, the use of passive voice in "is placed" detracts from the active recommendation style preferred in clinical guidelines.

Interestingly, the author chooses to omit semicolons; however, the list of toxicities could be punctuated more decisively; this would aid readability; moreover, the frequent use of commas creates a breathless rhythm; a balanced approach is advisable.

From an ethical standpoint, prescribing a drug with such a toxic profile demands a heightened sense of responsibility.

Patients deserve transparency and a clear outline of monitoring obligations.

Neglecting this could be construed as negligence.

In clinical practice, I have found that a structured follow‑up schedule-TSH at baseline, 3 months, then biannually-helps catch thyroid shifts early.

Coupling this with patient education about symptoms such as fatigue or weight changes empowers self‑monitoring.

Additionally, a low‑dose maintenance strategy (e.g., 100 mg) can reduce cumulative toxicity while maintaining efficacy.

Honestly, I think we’re over‑hyping amiodarone’s benefits.

Why not just go straight to ablation when it’s available?

Drug therapy feels like a stopgap, and the side‑effects are a real pain.

Just saying.

One must acknowledge the elegance inherent in a multi‑channel agent, yet the specter of iatrogenic sequelae cannot be dismissed.

Clinical stewardship necessitates a judicious appraisal of risk versus reward.

The pharmacokinetic latency demands patience, a virtue scarcely practiced in emergent settings.

In light of this, a calibrated approach-initial bolus, vigilant ECG surveillance, and staged tapering-emerges as prudent.

Conversely, indiscriminate deployment betrays a reckless disregard for long‑term morbidity.

Thus, the therapeutic narrative should elevate caution to a principle rather than an afterthought.

It’s encouraging to see the data presented so clearly.

Ensuring regular lab checks will make the therapy safer for patients.

Thanks for compiling this useful overview.